“Around the house with a lantern to look at the sleeping children and put on an extra cover. The miser’s hour for a mother—she looks at her gold and gloats over it!”

“Around the house with a lantern to look at the sleeping children and put on an extra cover. The miser’s hour for a mother—she looks at her gold and gloats over it!”

Anne Morrow Lindbergh, WAR WITHIN AND WITHOUT, p. 223

I love this image of Anne. It was 1941 and Charles was away on a trip. She was alone with their three young children in their small rented cottage on Martha’s Vineyard. I can imagine her creeping through the house late at night on her way to bed after she’s written in her diary. She pulls the edges of a sweater draped over her shoulders closer to her throat against the evening’s chill with one hand while she holds a lantern with the other. The children will need extra cover.

As she spreads an extra blanket over each one she pauses to look at the face of each sleeping child: Jon. Land. Anne.

What is it about a sleeping child? There is nothing like it to a parent. For one thing, no matter what he or she was like during the day—he could have been the reincarnation of Dennis the Menace—all melts away and is forgotten. The sight of a child’s face in slumber will do that. It is all vulnerability and sweetness.

My own son is eleven now and nearly as tall as I am. I am aware every day of how quickly he is growing up. But when I steal into his room for a last look at night and see his face resting in profile on his pillow, I am struck by how young he really is. Void of expression his features soften and remind me of the little face of not so long ago, emanating trust and innocence—and I realize that despite his rapid changes he has not been on this planet for very long at all.

Gazing at the face of my sleeping child is like time freezing for just a little bit. I get to behold, for a moment, the child he has been in the person he is becoming. Perhaps this is why Anne likens the experience to a miser gloating over his gold. Having lost a child, she knows the transitory nature of life.

Part of each of us, down deep, wishes we could hold onto our children and keep them young forever. We want to keep them close and safe. But we also know, down deep, that they will only be in our care for a time. They are a gift to us only temporarily. We treasure them, we let our hearts fill at the sight of them, we do all we can to enable them to blossom and grow. And then we open our hands, and—when they are ready—we let them go.

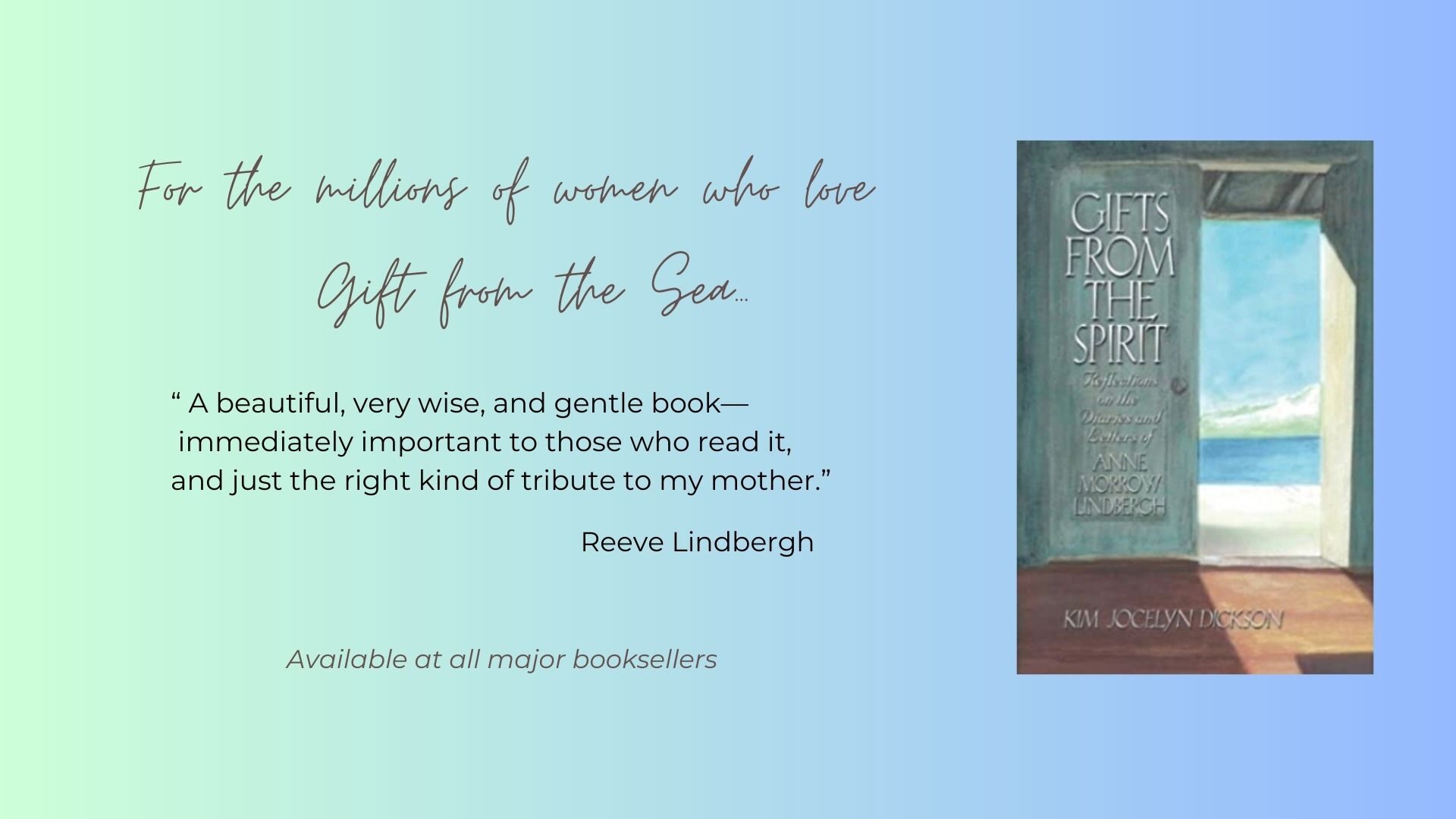

Excerpt from Gifts from the Spirit: Reflections on the Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, by Kim Jocelyn Dickson