Your summer place. Have you ever worried that you might not get back there?

Your summer place. Have you ever worried that you might not get back there?

“I am writing you in the desperate feeling that we will never get to North Haven. I have felt superstitious about it from the beginning because I have counted on it overmuch all summer long: the quiet and apartness and all of you, and the feeling of being completely alone and natural and oneself…”

Anne Morrow Lindbergh: HOUR OF GOLD, HOUR OF LEAD, p. 72

Anne was a newly married bride of twenty-four when she wrote these words to her mother. After the wedding and honeymoon in May she and Charles had barely touched back down to earth. His involvement in the aviation industry beckoned him from all quarters of the country. It was an exciting time for Anne, joining him in these ventures. She was meeting new people, seeing parts of the country she’d never seen before, and adjusting to life with her new husband. But she missed her family and longed for something familiar and secure in the midst of her new transient life.

Since she was a young girl, Anne had vacationed with her family in the summer on the island of North Haven, just off the coast of Maine. Their large summer “cottage” overlooked Penobscot Bay with a view to the blue Camden Hills on the mainland. For Anne, North Haven offered a retreat, a chance to be with her family away from the usual rhythms of life. Whether North Haven delivered long, lazy summer days in the cool clear sunshine or cozy indoor hours by the fire as squalls swirled outside, the Morrow summer home was a refuge. Here, Anne’s parents were relieved from some of the pressures of their busy lives and the family was free to simply be.

This first summer of her marriage Anne feared she might not get there. For the first time she experienced the tug of the needs of her husband on one hand and the pull of her family on the other. It was a tension she would feel always. Becoming caught in what others close to her wanted from her, to the extent that she had difficulty claiming what she wanted for herself, was a familiar place.

In the midst of this dynamic, however, I’m sure that Anne herself longed to get back to North Haven that summer.

If you’ve ever been to North Haven you’d understand why.

When I lived on the East Coast I had a friend whose family owned two summer cottages on North Haven. My friend, Laurel, had grown up spending summers on the island, just as Anne had. One summer she invited me and a few other friends to go to North Haven for a long weekend. I was just discovering Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books, so I already knew of the island and was thrilled for the opportunity to go.

It turned out to be beyond my ability to imagine. A sign posted along the highway just past the state line says: “Welcome to Maine: The Way Life Should Be.” That captures perfectly the way I have come to feel about North Haven. Over the next several summers, the island would be a yearly vacation retreat for me and a group of friends from Princeton.

Regardless of the weather, North Haven was magical. Otherworldly. Whether cloudy and rainy and shrouded in mists of purple, blue, and gray, or bathed in sunshine and cool crystalline air, the deep green pines stood out against the wild rocky shore and beckoned you to come closer, go deeper. The scent of pine and sea filled your lungs and you felt more alive than ever.

Our trip was the same from year to year. The ferry delivered us into the arms of the harbor and gently let us go. We drove through fields of blue lupine and grazing cows to get to our cottage. The lilacs by the porch would still be in bloom. I’d cut some for the table that night. We’d unpack, stopping every couple of minutes to look out the bedroom window into the cove just yards from the front door. Across the cove, the sun would just be beginning to dip behind the Camden Hills in a spectacular display of reds, oranges, pinks, and magentas. We’d all stop what we were doing to rush out to the dock to watch. This became one of our rituals on the island.

We had others, and a sort of routine emerged. Since there were so few distractions on the island we’d make up our own. First were the lazy mornings. People would rise whenever they felt like it. Someone would make coffee, and there were usually a few people sitting on the porch drinking it, reading novels, and having leisurely conversations. Someone might cook a big breakfast, or we might fend for ourselves when hunger struck. Grape-Nuts and muffins were perfect. Once children came along, breakfasts became a bit more official. After breakfast, someone might take a walk or a bike ride. Or go sailing. Or row across the cove to the spit of rocks to dig mussels for dinner. Or sunbathe. The water in the cove was too cold to swim in, but Laurel took one quick dip every year. She’d been doing it since she was a little girl.

Lunch was a loose affair, too. A pot of homemade soup sat on the stove, ready whenever we were. Afterward there might be naps outside in the sun. Someone might make a trip to town to restock supplies at Waterman’s, the only general store on the island, or to pick up lobster, fresh from this morning’s haul, for dinner that night. We’d scatter alone or in couples or small groups to do whatever we felt like. But late afternoon brought a ritual nobody wanted to miss.

As the sun dipped lower and the air grew cooler, we pulled on our sweaters and took up our mallets. The lawn in front of the cottage that sloped to the edge of the cove became our croquet court. It was happy hour. Steve would roll out the old battered wooden wagon of some child long ago and set up the bar. Gin and tonics. Margaritas. Take your pick. Music rolled out over the lawn–James Taylor, maybe, or the soundtrack to “The Big Chill.” As a matter of fact, sometimes we felt we were living “The Big Chill.” We’d sip our drinks; we’d savor the sunset; we’d dance and sing along to the music; we’d have no mercy for each other on the court, sending each other’s croquet balls off into oblivion and evoking the ooga-booga charm of protection around our own (this involved making the sign of the cross over your croquet ball and chanting ‘ooga booga’) whenever threatened. We were silly and laughed at nothing and everything. Whoever was responsible for dinner that night would be inside preparing the lobster and it would be ready soon. Life was good.

Our days took on a lovely timeless rhythm. Our spirits adapted to our surroundings and we breathed in time with the wind and the tides and our most basic needs. Released from the pressures of our day-to-day existence, we felt more fully alive than ever. Our sense of life was heightened–perhaps because we had slowed down enough to appreciate it.

The special group of friends are scattered all across the country now. We had been in graduate school together, some of us worked at a summer camp together, some of us had been to college together. One of us has died, children have been born. We’ve all moved to new stages in our lives. But none of us will forget those days. Even in the midst of living them I think we all knew how extraordinary our days on North Haven were. We were young, on the threshold of the rest of our lives, and our playground was one of the loveliest places God ever made.

Mystical, enchanting, ruggedly beautiful, North Haven is a taste of what heaven might just be like. Or at the very least–the way life was intended to be. I can understand Anne’s worry that she might not get back there. But she did. And as she would recount later in Gift from the Sea, she managed to find “North Haven” for herself in other places too. Places where she could retreat to and, in letting go of the demands of daily life, tap into her inner springs once again.

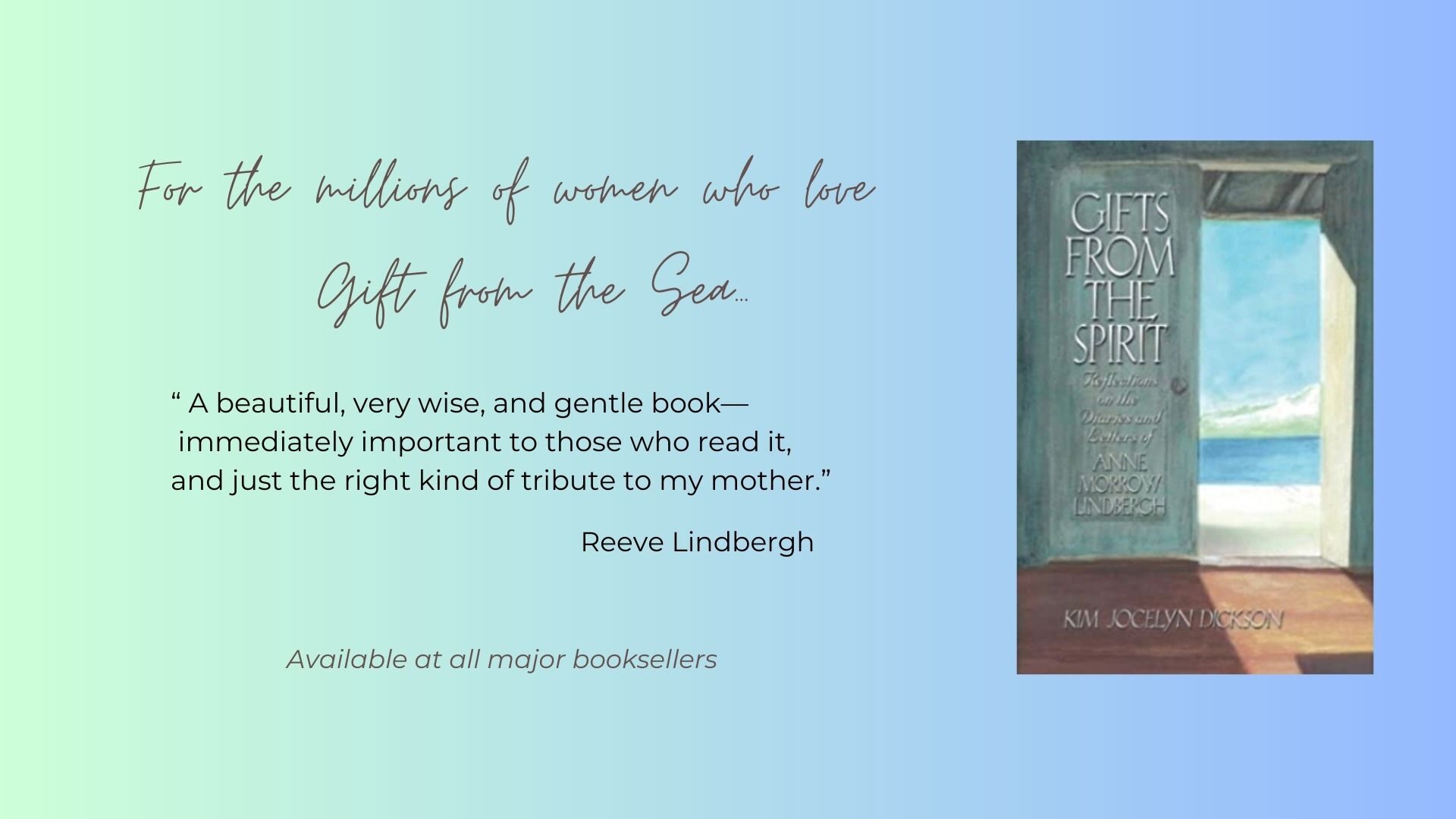

[Excerpt from Gifts from the Spirit: Reflections on the Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh]