“You write, and if there is one person in the world who you are sure will understand it is enough, and what you write glows with some kind of inner life, some life of its own.” (Anne Morrow Lindbergh: War Within and Without, p.447)

[Over the years since the publication of Gifts from the Spirit: Reflections on the Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, I’ve worked on some other essays reflecting, specifically, on Anne Morrow Lindbergh and writing. This one captures a memory I’ll never forget.]

When Anne learned the news that Antoine de Saint Exupery had been killed flying for the French resistance in World War II she confided her feelings of futility about continuing to write into her diary. Anne knew that above all others Saint Exupery had deeply understood her work—he got her. She’d written The Steep Ascent—her 1944 novella—to him. Anne’s meeting with Saint Exupery in 1939 had emboldened her to attempt this first work of fiction. Based on an true harrowing incident that occurred while flying over the Alps with Charles, The Steep Ascent is a parable that illustrates Anne’s belief, shared by Saint Exupery, that life is lived most fully when one is conscious of the shadow of death. Her hope for its publication was that it would reach him—as a letter might—but it never did. He died too soon. What was the point of writing now, she wondered. Who else could understand as he could?

Many things motivate people to write. Money, fame, immortality, recognition, self-expression, pure love of the craft—any or all of these may fuel a person. But I believe that underlying all these things one who has the soul of a writer writes for a more fundamental reason: the longing to connect. No matter the subject matter. Whether you have a story to tell or a subject to bring to life, you write because you want to touch someone—you long for communion.

While working on the reflections for Gifts From the Spirit I was aware of writing to please myself. This may sound strange, but when you’ve lived most of your life trying to please others and finally are able to embrace the futility of that it’s enormously liberating. I had learned so much in the twenty years since I’d first imagined writing the book to actually doing it. In writing the reflections I was reminding myself of what I’d learned to be true.

I later realized there was a little more to it than this. While I didn’t really write to please anyone but myself, there were certainly people who I wanted to like what I wrote. First on that list would have been Anne herself. I was aware, though, that she would never read my book; she died the year before its publication. But right behind Anne on my list was her daughter.

Reeve Lindbergh is the youngest of the six Lindbergh children. Of the four remaining siblings, Reeve is the only daughter and the most actively involved in supporting the legacy of her parents. She is the author of several children’s books as well as books having to do with her famous family. I’d read her work over the years and it was clear to me that she’d struggled with who her parents were and who she was in relation to them, and that she was an aware, sensitive person, as her mother was. I hoped that one day I would meet her.

At my very first meeting with Roy Carlisle in San Francisco he suggested I contact a member of the Lindbergh family to explain my proposed book. He felt it might be important to have their support in getting permission to use quotes from Anne’s diaries and letters. I knew just which family member that should be.

A few weeks after I sent off a letter to Reeve, care of her publisher in New York, I came home to a message from her on my voicemail. She not only liked my idea for the book, she gave me the name, address, and phone number of her mother’s editor at Harcourt, Brace in San Diego and told me I should let the editor know that she, Reeve, had recommended I speak to her. She also left her own number at her home in Vermont, telling me to feel free to phone her if I wanted to. Her voice was warm, enthusiastic, and kind—it was clear she wanted to be helpful. It took a couple of days for me to recover from the shock and thrill of receiving this message. Then I worked up my courage to call her back.

“She of all people would know whether I had captured something of her mother’s essence in my reflections. She seemed to feel I had, and that meant the world to me.”

I learned that Reeve loved her mother’s diaries and letters best of all her published work and so was pleased to support a work that celebrated them. We spoke for several minutes and all the while I was speaking calmly and normally–I hope–my feelings were jumping up and down inside of me, doing back flips and cartwheels: Oh my God. I’m talking to Reeve Lindbergh! At the end of the conversation I promised to keep her posted on how the project developed.

Once my manuscript was complete, I sent it to her. Not long after, she sent me a handwritten response. This was not the first time I’d received a note from her and wouldn’t be the last. I have a file marked “Reeve Lindbergh” where I keep this treasured correspondence. Her lovely and gracious letters came on heavy ivory note cards with her letterhead printed in black at the top. This time was no exception. My heart was in my throat as my eyes slid over the now familiar black-inked half print, half script. She wrote:

How very touched my mother would be, as I am, to know that you have taken her words and gone forward with them into your own unique and important wisdom, out into the world. Your own understanding is extraordinary, your own words so beautiful—“The unbearable is latent everywhere. Even in beauty.” She would love that!

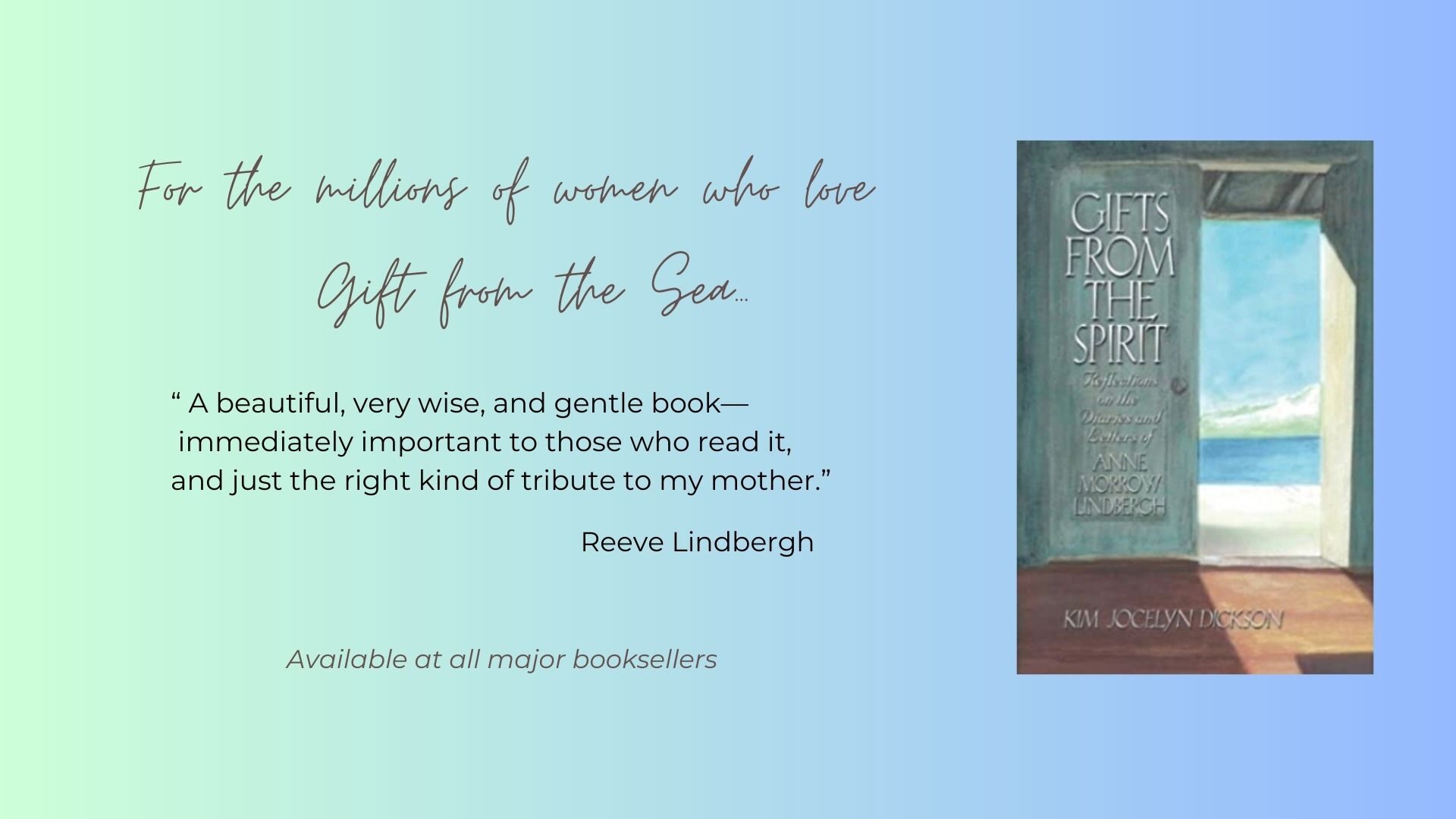

Reeve Lindbergh had quoted my own words back to me! She wrote some other wonderful things about my book too, things that she gave my publisher permission to quote to use for promotional purposes.

I was flooded with warmth, gratitude, and a deep sense of satisfaction. Reeve’s opinion was important to me because I knew I could trust her response. She of all people would know whether I had captured something of her mother’s essence in my reflections. She seemed to feel I had, and that meant the world to me.

The summer before my book’s publication I finally met Reeve in person in her hometown in Vermont. Knowing I would be in the east, visiting friends in the New York area, I had called ahead from California and invited her to meet me for lunch. I would happily make the drive to Vermont from New York. To my delight, she accepted and suggested an inn where I could spend the night when I got into town. At noon the day of our meeting, I was in the lobby of the hotel, pacing as nervously as a teenager before a blind date, waiting for her to pick me up—something she had graciously offered to do. In a moment, Reeve came bursting through the front door, all smiles and warmth, and full of apologies for being just a few moments late. Her daughter had just returned from a trip the night before, and they’d sat up late talking. She shooed away my protestations about taking her away from her with a laugh; she was still in bed! They hadn’t even unloaded her gear yet, she said as we headed into town, waving her hand toward the backseat of her Jeep that was a jumble of duffle bags and jackets.

Dressed in a cool periwinkle summer dress with a simple golden chain around her neck and gold hoops in her ears below her short curly blond hair, Reeve was down to earth, extremely easy to talk to, and a very good sport, even posing for a picture with me at the bookstore where we stopped for lunch. I felt a slight hesitation in asking for one when she introduced me to her friend, the bookstore owner, but I knew I would always regret it if I didn’t. There was a dream-like quality to this meeting and I was afraid that if I didn’t have a picture, I would suspect later that I had made it up.

Once introductions were over, we settled into our booth at the café and ordered iced teas and smoked salmon salads. I had read over the menu, registering absolutely none of it. Food was the furthest thing from my mind, so having no appetite, I simply followed her lead. As the waitress retreated, Reeve folded her hands and directed her china blue gaze at me across the table.

Now. What are we going to do to help you sell your book?

I was struck speechless for a moment, but it wouldn’t be the last time that day.

The conversation that followed included everything from the sharing of names, phone numbers, and addresses of people she felt I should contact, to discussions about future writing projects—hers and mine—to what kinds of books we each liked to read. I learned that Reeve is partial to mysteries.

Occasionally, moments of awareness would flash across my consciousness, and I’d realize I was seated across the table from the daughter of two icons of the twentieth century. Two icons that I felt I knew intimately from reading everything they had ever published. The sense of the surreal vanished quickly, however, as the normalcy of simply enjoying our salads and iced teas and discussing everything from publishing to our sons who are about the same age brought me back to the present. And all the time the laundry of her returning daughter was sprawled across the backseat of her green Jeep Grand Cherokee that waited for us outside at the curb—just like any mother’s might be.

Afterward we lingered in the bookstore for a bit, chatting and browsing through the children’s section, where we saw several of her titles. Just as I was thinking that our time together was drawing to a natural conclusion and that we would soon head back to drop me off at my hotel, Reeve asked if I would like to come out to her farm to see the home where her mother had spent her final days.

Things were not feeling so normal anymore.

“Reeve led me inside the cozy tent-shaped cottage that felt as if her mother had been there as recently as that morning. What is this thing that is presence and yet not presence?“

When in her nineties Anne had become debilitated by dementia and a series of strokes that rendered her unable to communicate or care for herself, Reeve’s husband designed an A-frame that duplicated the chalet that had been a second home to her in Switzerland for many years. Then he built it on their farm property just yards from their own home. It was here that Anne spent her final days with round the clock caregivers and her daughter and her family, and it was here that she died. Reeve wrote poignantly about this difficult chapter of their lives in her book No More Words: A Journal of My Mother Anne Morrow Lindbergh.

I was mildly stunned. Agreeing to meet me for lunch had been so kind of Reeve. It was more than enough. This was an extension of grace I had not expected.

Our easy conversation continued unabated on the drive out to her farm. We swapped impressions of my hometown, St. Louis, the city whose name was borne across the Atlantic on her father’s plane, the city that cherished all things Lindbergh and welcomed her as one of its own. She also told me about a theatre company there that once invited her to a premiere of a play about the kidnapping and murder of her oldest brother—as if this was something she would actually be interested in seeing. We shook our heads in mutual dismay at this. The flow of our talk slowed just as we pulled up to the chalet and parked. Then, silence descended.

The sense that I was treading on sacred ground was palpable, and I became very quiet. Reeve led me inside the cozy tent-shaped cottage that felt as if her mother had been there as recently as that morning. What is this thing that is presence and yet not presence? [1] I thought of Anne’s apprehension of her lost baby boy so many years before as she touched the clothing and playthings left behind in his empty nursery. In the same way, she now seemed to be present in this space so full of her things. We walked through the door, past the tiny kitchen and into the sitting room where a worn and comfortable blue and white patterned sofa rested under a large picture window that looked out onto the Vermont countryside. The mantel over the fireplace was lined with feathers, stones, and shells. Dozens of shells.

Reeve walked over, picked one up, and pressed it into my hand. Here, she said gently.

Wordlessly, I accepted the gift and my fingers closed around it. The smooth thick cone shell fit perfectly into the palm of my hand and I clutched it as she led me from the living room into the room that had been Anne’s bedroom, the room where she died.

Here was the window that looked out onto the tree where, despite the bleakness of February, birds came and perched on its snow-laden bare branches just after her passing. First the chickadees, then the juncos, then the bluejay. All paying their final respects, all saying goodbye.[2] She had loved birds and taken joy in watching and feeding them daily.

Next to the window was her bed, a single bed, and I thought of how she had lived for more than twenty years as a widow alone. Framed photographs seemed to fill the room and covered the entire surface of her desk. Here were the real people I had only read about: Charles, their children, their grandchildren, Anne’s own parents and brother and sisters—many of them long gone—only their images witnesses to her passing. I stood on the edge of this small room taking it in as Reeve stood quietly in the doorway, and was overcome again with a sense of Anne’s presence as tears welled in my eyes. I was standing on holy ground. Wordless, still, I could only breathe and grasp my shell tightly.

Eventually Reeve took me down some carpeted stairs to the basement, a finished room with floor to ceiling bookshelves that was Anne’s library, and the transcendent spell was broken by the unwelcome intrusion of my cell phone. I quickly apologized and switched it off. As I perused the titles, many of which were first editions of the Lindberghs’ own books just like the ones on my own shelves at home, Reeve explained that many of the books would be donated to a local Buddhist meditation center. I remembered reading in her book that some of Anne’s caregivers in her final years had been associated with that center.

I have no recollection of what we spoke of later on the drive back to my hotel. I do remember, though, that when Reeve and I took our leave of each other at the entrance to the inn amidst an embrace and my murmurs of profound thanks, Anne’s shell remained tucked into the palm of my hand as if it simply belonged there. It had never occurred to me to put it into my bag. Like a small child who receives an unexpected, too-good-to-be-dreamed-of treasure, I couldn’t seem to let it go and held it firmly all the way back to my room.

[1] Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1973), p. 258.

[2] Reeve Lindbergh, No More Words: A Journal of My Mother Anne Morrow Lindbergh (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001) p. 169