“The feeling of exultant joy that there is anyone like that in the world…Clouds and stars and birds–I must have been walking with my head down looking at puddles for twenty years.”

“The feeling of exultant joy that there is anyone like that in the world…Clouds and stars and birds–I must have been walking with my head down looking at puddles for twenty years.”

Anne Morrow Lindbergh, BRING ME A UNICORN, p. 99

Anne was a twenty-one year old senior at Smith when she had an encounter that would change her life. It was December of 1927 and the Morrow family was spending the Christmas holidays together in Mexico City, where Anne’s father served as U.S. ambassador. It had been just seven months since Charles Lindbergh made his historic solo flight that rocked the world. Now, at the invitation of Ambassador Morrow, and in the interest of strengthening relations between the United States and Mexico, Lindbergh was coming to spend the holidays with the Morrow family. And he was about to rock Anne’s world too.

Until this point, Anne’s world had included only the New England upper class–the well-to-do, highly educated, and intellectual—her parents’ people. Charles was different and he took her breath away. This shy “clear, direct, straight boy”[i] who said little but accomplished much, stood in sharp contrast to all the other men she’d known. Next to Charles—an independent, courageous, sincere, forthright man of action—all the articulate, well-read, sophisticated, pretentious suitors Anne had known paled. His directness, his economy of words, his lack of pretense, and his sheer masculine presence bowled Anne over.

In her world people read about and discussed things. In Charles Lindbergh’s world, people did them.

The attraction between Anne and Charles was instantaneous and mutual, but it would be several months before Charles called for a date. In the fall of 1928, he invited Anne to fly with him. Within a few months they were engaged, and in May of 1929 they married.

Despite their whirlwind courtship, Anne was racked with doubts, and she agonized over their relationship: “It is a dream and a mistake. We are utterly opposed.” [ii] She was introspective; he was a man of action. She was an incessant reader; he rarely cracked a book, his idea of good poetry was that of the lowbrow, sentimental Robert Service, and he didn’t even get the cartoons in The New Yorker magazine. She was Ivy League; he was a college dropout. She was a dreamer; he was practical.

Yet underneath it all there was a powerful attraction. As their daughter Reeve said years later, their marriage was inevitable.[iii]

Indeed it was. For what was at the heart of the attraction between Anne and Charles was a deep, unconscious connection: their emotional similarity.

Years later Anne described a conversation she and Charles had with the Duke and Duchess of Windsor at a party in Paris before the war. The four compared notes on the isolation and indignation they suffered because of their fame: “…a pair of unicorns meeting another pair of unicorns.”[iv]

Anne’s self-identified image of the unicorn—an elusive magical creature—was one that would recur in Anne’s literary work. The volume of diaries and letters that contained her first meeting of Charles was entitled Bring Me a Unicorn. Her only published volume of poetry, The Unicorn, included a long poem called “The Unicorn in Captivity”, which was inspired by a tapestry from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In the poem Anne described a hunted, fenced in, bound, and wounded creature who found his freedom internally—an image that resonated deeply with her.

The themes of captivity and freedom surfaced again and again in the Lindberghs’ lives. This appeared to be because of the relentless pressure of fame. Incessant publicity held them captive, rendering them unable to move freely. Flying and escaping to far corners of the world granted them the freedom they craved.

I believe that for Anne and Charles, though, the pull toward freedom and away from captivity stemmed from origins far deeper than the world of fame they inhabited as adults. Their identification with the wounded creature was rooted in the pain and “captivity” of emotional isolation they each experienced as children.

Charles’s parents were estranged during his childhood, but they never divorced. At a young age he was forced to assume adult responsibilities and was expected to grow up quickly. One senses that there was no one really there to take care of him. Living in a chronically painful situation, Charles learned early not to feel things. Action became his means of escape.

Anne had a family that appeared to offer every possible good thing to its children, but her childhood, too, was marked by emotional deprivation. She was expected to grow up to be just like her mother—a woman who was uncomfortable with her own feelings and who avoided them through nonstop social activity and philanthropy. Anne was not supported in becoming herself.

When Anne and Charles met that December in Mexico, each of them unconsciously recognized themselves in each other. A unicorn meeting another unicorn. A powerful attraction.

In her novel, The Names of the Mountains, Reeve Lindbergh told a fictionalized version of her aging mother’s gradual decline. Anne—through the character Alicia in the story—said marriage was “…both an escape from and a reflection of the marriage in which each partner was raised.”[v]

For Anne, marriage to Charles was certainly both. He offered an escape from the intellectualized, protective, and confined world of her parents. Charles offered adventure and a chance for her to shift from the life of the mind to the life of the body. Anne’s decision to marry Charles stretched her in ways she might never have known had she not taken the leap.

What she didn’t realize, though, was that she was marrying into the same emotional reality that she had grown up with. Life with Charles may have looked different externally, but emotionally, she would discover, he was every bit as detached as her own parents.

The mystery of attraction is really not so mysterious after all. More and more, I believe that we are attracted to people—romantically or otherwise—at this deeply unconscious level. There is something about the person we are attracted to, below the flow of words and actions, that—no matter how different from us they may appear—is familiar. That reminds us of what we already know.

Not only do we find relationships that replicate the emotional reality we knew growing up, we also manage to create circumstances that repeat it, too. Anne married a man who mirrored the emotional distance and exacting demands of her parents. She also found herself in circumstances, due to her celebrity, in which she had to struggle against feelings of isolation, misperceptions, and captivity–evoking a sense of reality not unlike that of a little girl whose identity and value is not perceived accurately by those around her.

As adults we recreate the hurts of childhood to get a second chance to work them out and be free of them. And we do all this without realizing it, of course. What is deepest and truest in us is wiser than our conscious self and longs for us to be healed.

But healing doesn’t come automatically, nor does it come easily.

We gain our second chance only when we have the courage to allow this deeper knowledge to come into the light. This requires the slow, painful work of choosing to understand ourselves and the reality of our history. Only then can the present circumstances—the marriage, the difficult situation—be apprehended in its proper perspective and be transformed.

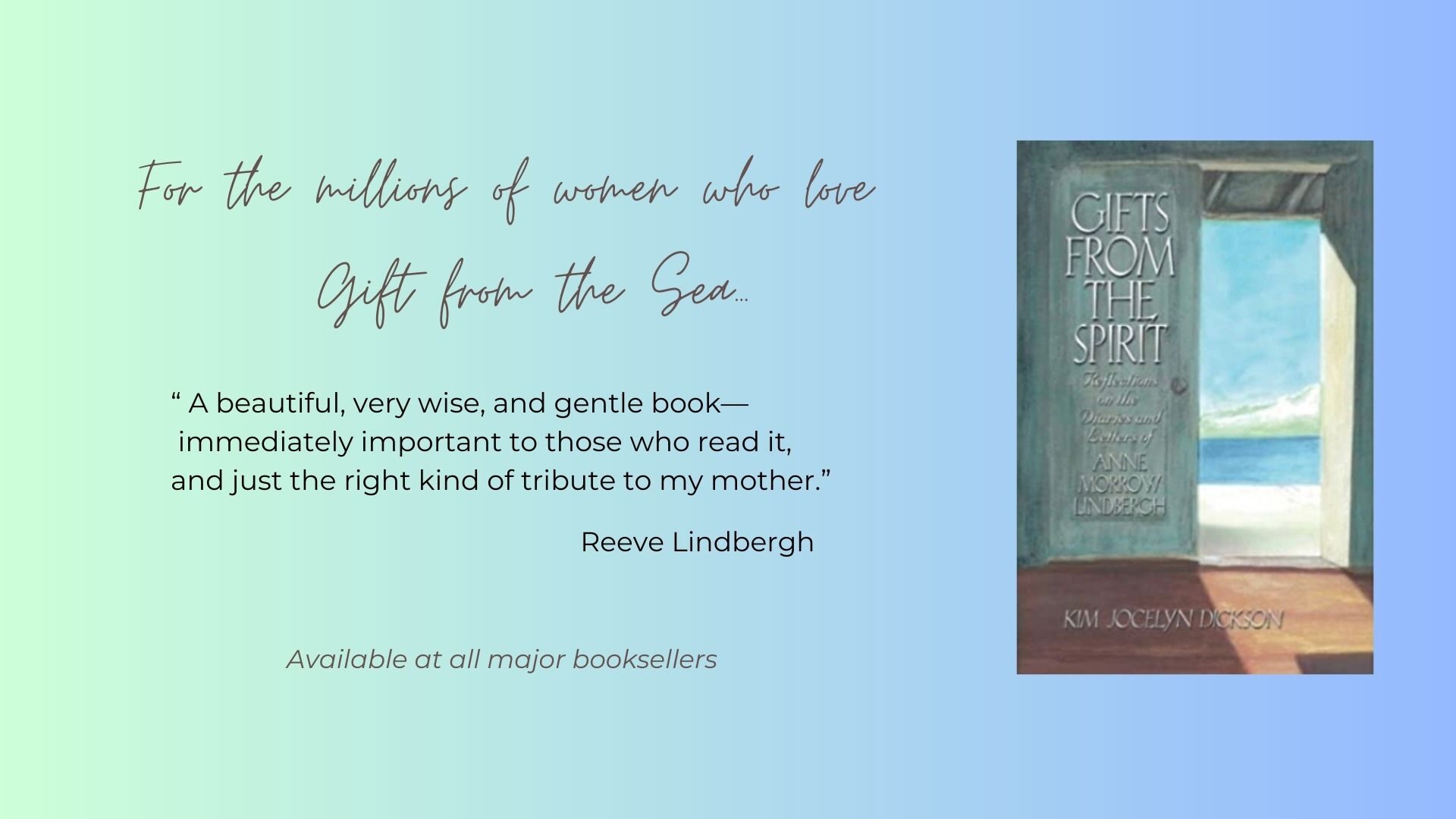

Excerpt from Gifts from the Spirit: Reflections on the Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, by Kim Jocelyn Dickson

[i] Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Bring Me a Unicorn (New York, Harcourt Brace and Jovanovich, 1971) p. 99.

[ii] Ibid. p. 224.

[iii] Reeve Lindbergh, interview in “ Charles Lindbergh and Anne Morrow Lindbergh” A&E’s Biography, April 2, 2000.

[iv] Anne Morrow Lindbergh, The Flower and the Nettle (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976), p. 510.

[v] Reeve Lindbergh, The Names of the Mountains (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992) p. 101.